Git Flow By Example: Writing Down Your Version Control Process

What does your version control process look like?

Every PCI auditor asks this question on Day One of every audit. In far too many cases, the answer is just two words: Git Flow, usually backed up with this exact hyperlink, or maybe this one.

Pro Tip: Not a great way to start an audit!

The reason this is a bad answer is that these documents are purely aspirational. They describe some rather general key characteristics of a Git Flow process. But what they do not describe—because they can’t—are the very specific characteristics of your Git Flow process.

And that’s what the auditor is looking for, because if you haven’t written your project’s version control process down in all its unique glory, then you don’t have one!

Custom By Definition

Your specific Git Flow process depends on a lot of things, including:

-

Your application architecture.

-

Your application technology stack.

-

Your DevOps stack.

-

Your team’s size and composition… specifically its capacity to customize your DevOps stack.

Any version control process worthy of the name needs to take all of this into account, and then—wait for it—it has to be written down!

In 2024, odds are that you’re an Agile team, and the concept of iteration is not foreign to you. For sure, you are accustomed to iterating over code. If you’re doing it right, you also iterate over requirements.

So consider that your written-down version control process is just another requirement. It’s a meta-requirement that governs the architecture of the factory that ultimately delivers your production code. And that requirement is itself implemented in code, in the form of your DevOps pipeline.

Once your process is clearly written down and subject to frequent, planned iteration, expect your team to find tighter, faster, more efficient ways to generate higher-quality code!

A Model Git Flow Document

The Git Flow document below is one I’ve used in the context of a microservices project.

I do not mean to suggest that it is wholly appropriate for your project, even if yours has a microservices architecture! As I observed above, any such plan depends critically on platform and team characteristics that will be unique to your situation.

So what I hope you will derive from this example is a sense of the form and the level of detail that goes into a version control plan worth iterating over.

For the record: The organizations where I use this approach routinely hit 100% in their PCI audits! 🚀

Git Flow @Karmaniverous

Microservices & Semantic Versioning

The Application has a microservice architecture.

The front end is a single repository, independently deployed and version-controlled. At this writing, the back end consists of 16 distinct services. These services are also independently deployed and version-controlled. They are largely self-contained, and only interact with the front end and with each other across their respective API Gateway interfaces.

The Application as a whole is assigned a new version number following each release to production. Release notes for these versions aggregate changes across independently versioned components, but is essentially a business-facing property of the Application and is independent of the version control system. Application version is not discussed here.

Every service in the Application uses Semantic Versioning, like 1.2.3. The left-most value in a semantic versioning tuple is the major version. An Application component advances by a major version when there has been a breaking change.

Most Application services communicate with other services, and the front end communicates with most of them. Every service maintains a version-controlled file that indicates which major version of each of these services it is compatible with. Here is an example of this file in a back-end service, and here is the code that serves the same purpose on the front end.

The two document links above are non-functional. They are placeholders for the actual locations of these files in the respective repositories.

Since each service is looking for a specific major version of every service it connects to, we can refine our definition of major version within the Application:

A service must advance to a new major version when it makes a change that renders it no longer compatible with other services that currently call it.

Instance & Environments

An instance of the Application is a complete set of Application services that support one another in a mutually consistent manner. No one Application instance should interact with any other instance.

An environment is the set of resources representing a deployed instance of the Application. Since each service is an independent entity, each must be deployed individually into an environment and may to some degree be tested in isolation. All services (including the front end) must be deployed to an environment for it to be fully operational.

Current examples of environments include:

-

Production

-

Release

-

Development

-

Preview environments like

preview/baliandpreview/texas

With respect to a given repo, every environment is major-version specific! If the user service is in v2, then unless one has been deleted, the following user APIs are available to be combined into the dev environment:

api-user-v0-devapi-user-v1-devapi-user-v2-dev

Every Application repository has an env directory whose contents define every supported environment to which that repository’s code deploys. The project CLI leverages these files to facilitate environment-specific operations.

Each environment is “connected” to a branch with the same names in every service and front-end repository. When code is pushed or merged to this branch, it is automatically built and deployed to the respective environment.

Environments fall into two distinct categories:

-

Protected environments are connected to protected branches and can only accept updates via Pull Request, whose rules tighten as environments approach production. A protected environment can be both a source and a target of a Pull Request. For example, developer code can be PRd into

devand then fromdevto areleasebranch, while bugfixes on areleasebranch will usually be PRd back todev. -

Preview environments are connected to unprotected branches and will generally be assigned to an individual developer. The purpose of a preview environment is to validate that code changes build & deploy properly and to test them in the cloud environment.

Developers may merge freely INTO preview environments but should NEVER merge FROM them!

Git Flow in Microservice Land

Karmaniverous generally follows the GitFlow workflow. The Karmaniverous process differs in that GitFlow addresses the needs of a monolithic application, whereas the Application exists (so far) across 16 loosely-coupled, independently-versioned code repositories.

The local flavor of GitFlow takes this into account.

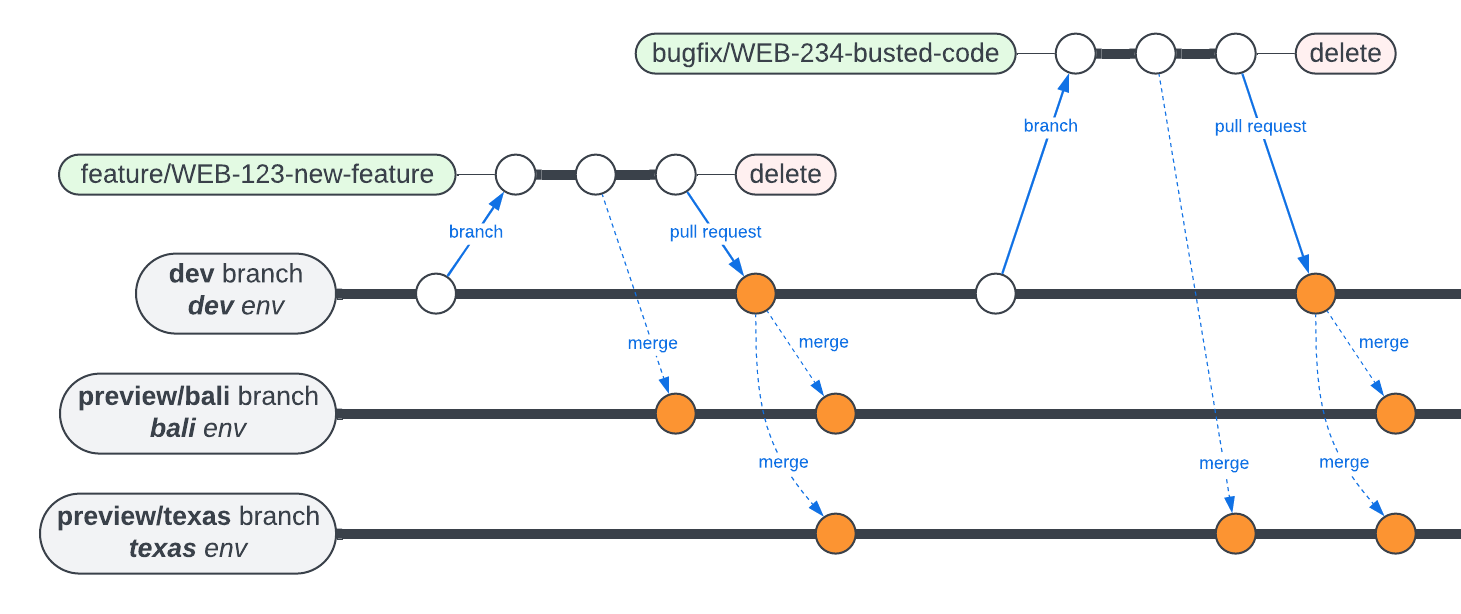

As you examine the commit flow illustrations below, remember this: each of these pictures only illustrates actions in a single repository!

In reality, a correlated change might involve more than one or even all Application repositories! Therefore, in order to keep things clear…

Correlated changes across multiple code repositories should use branches of the same name!

Branches across the Application fall into two distinct categories:

-

Persistent branches accumulate changes over time and are rarely or never deleted. Persistent branches support the

preview,dev,release, andprodenvironments. -

Temporary branches support the development of a feature or the repair of a defect and are deleted once no longer needed. Code from a temporary branch can be deployed and exercised in the cloud in one of two ways:

-

It can be merged or PRd into an environment’s branch, which will deploy it automatically.

-

It can be deployed directly into a preview environment from the VS Code using the CLI.

-

Feature & Bugfix Branches

The development of new features and the repair of defects in any code repo begins on the dev branch. It should follow these steps in the IDE (git syntax is flexible, so your version might differ):

-

git switch devto switch to the dev branch. -

git pullto sync with the remote branch. -

Is your preview branch consistent with

dev? If not—at least to the extent that it matters—merge every other Application repo fromdevinto your preview branch. -

git checkout -b branchnameto create a new local branch. -

git push -u origin branchnameto push it toorigin. -

Develop within

branchname. As required, deploy directly to your preview environment or merge to your preview branch to check your work. -

Merge to a preview branch to validate the deployment process.

-

Push your local changes to

originand PRbranchnametodev. -

Delete

branchnameonce it is merged intodev.

Some notes about branchname:

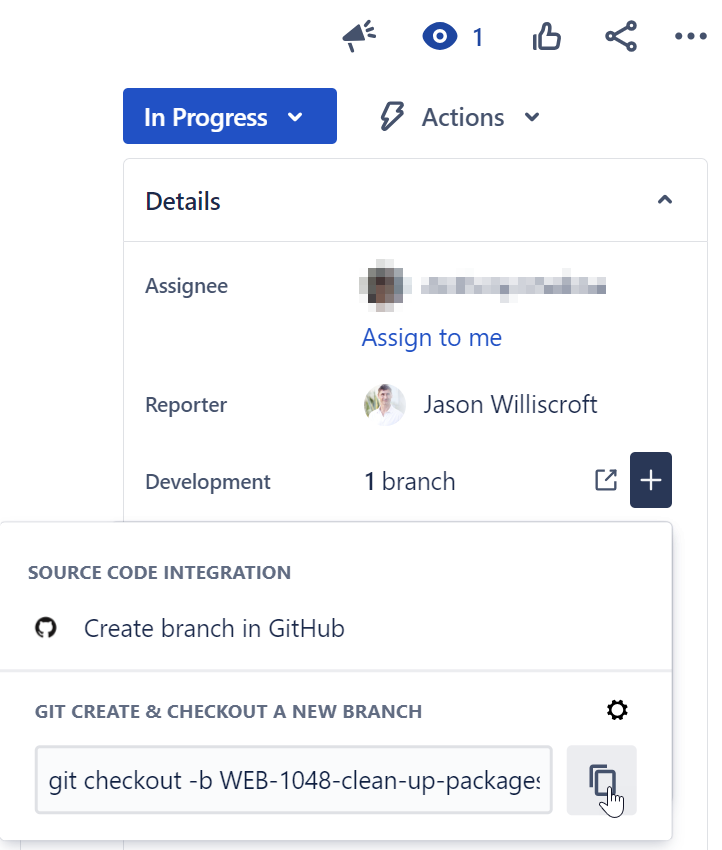

- Every Jira issue features a control allowing you to copy the code to create a related branch. This code branch has a name like

WEB-123-hyphenated-issue-summaryand is almost perfect:

-

Each branch name should be prefixed with a branch type token, like this:

feat/WEB-123-hyphenated-issue-summary. Valid issue branch type tokens are:-

featurefor feature branches -

bugfixfor bugs indevor areleasebranch. -

hotfixfor production bugs.

-

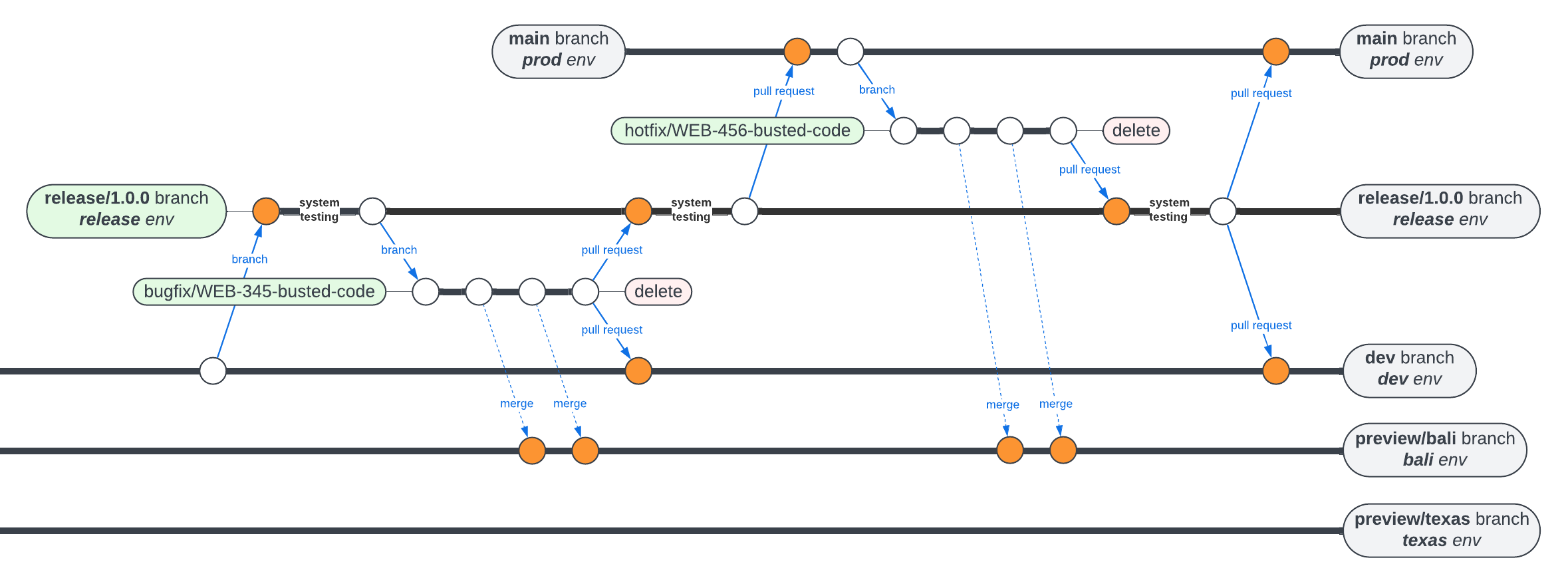

Release & Hotfix

As described above, every Application service (and the front end) is specified to be consistent with a specific major version of every other service it talks to.

When changes to a service render other services no longer able to communicate with it, it gets a new major version, which has the effect of deploying a new environment for the upgraded major version, while leaving the one for the old version in place! Once this happens, it is up to the dev team to migrate data and other assets into this new environment to prepare it to receive traffic.

Those other services remain connected to the previous major version until they are themselves updated (which may or may not require a new major version on their part) and pointed at the new major version of the service under consideration.

The event that kicks all of this off is the release. A release (nr release in the IDE) may only be run on the dev branch. It performs the following steps:

-

Runs the local build and all unit tests.

-

Updates the repo’s package version to indicate a new major, minor, patch, or pre-version.

-

Creates tag

major.minor.patch[-pre]in GitHub. -

Creates branch

release/major.minor.patch[-pre] -

Deploys the contents to environment

release, which will overwrite content of the same major version or deploy new assets if the major version has changed.

Code that has been elevated to the release environment should be subjected to extensive system testing. This is not yet automated, but soon will be.

Bugs that are discovered on a release branch should undergo the same bugfix process as described above, except that the source of the bugfix branch should be the release branch rather than dev. Completed repairs should be system-tested again and then PRd both to the release branch and back down to dev.

Once release testing is complete, the release branch can be PRd to main, which will trigger build & deployment into the production environment.

A bug discovered in production should generate a hotfix branch, just as a bug discovered in dev or a release branch should generate a bugfix. Repaired code should be PRd to the relevant release branch for system testing before PR back to prod and down to dev.

Rollback

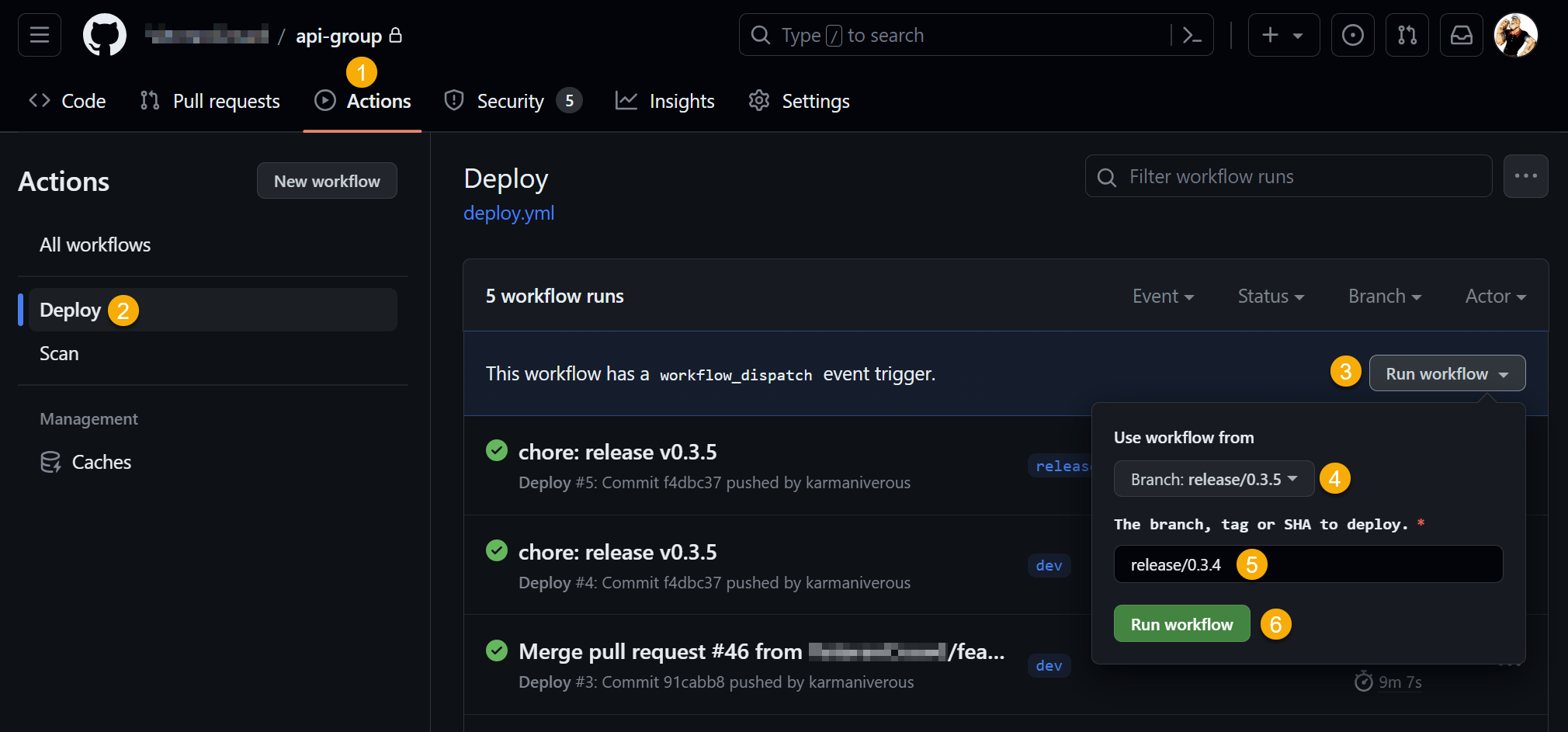

Any deployment environment can be rolled back to a previous reference (a branch HEAD, tag, or commit SHA) by manually running the GitHub Actions deploy action in the related branch.

A rollback does NOT affect code committed to the related branch! It only deploys an earlier version of that code into the cloud environment related to the branch.

To roll back a deployment related to any branch:

-

In the repository of interest, choose the Actions tab.

-

Choose the Deploy workflow.

-

Run the workflow from the workflow_dispatch trigger.

-

Choose a source branch associated with the target environment. In the example below, code will be deployed to the

releaseenvironment. -

Enter a Git reference for the code to be deployed (the example below rolls the release environment back to version

0.3.4). This can be:

-

A branch name (deploys the branch HEAD).

-

A tag (deploys the associated commit).

-

A specific commit’s SHA.

- Run the workflow.

release deployment environment to an earlier version.

Branch Naming Policy

The branch naming policy is enforced by a pre-commit git hook in every code repository.

All branch names must adhere to the following RegExp pattern:

^(dev|main|preview\/[a-zA-Z0-9]+|(bugfix|feature|hotfix)\/[a-zA-Z]+-[0-9]+[-][-_a-zA-Z0-9]+|release\/[0-9]+\.[0-9]+\.[0-9]+)(-[_a-zA-Z0-9]+)?$

Does the RegExp above seem… primitive? Git bash uses an archaic flavor of RegExp that does not include common tokens like \d and \w!

These are examples of valid branch names:

-

main -

dev -

preview/bali -

hotfix/WEB-1234-description -

bugfix/web-1234-description -

feature/WEB-1234-description -

release/1.2.3-0 -

release/1.2.3

These are examples of invalid branch names:

-

WEB-1234(needs a type tag & description) -

feature/WEB-1234(needs a description) -

foo(just wrong) -

preview(needs a preview designator) -

release(needs a version number)

Follow The Breadcrumb Trail

If you read the above document, you probably noticed that it depends critically on a bunch of tools & processes that are mentioned but not fleshed out here. They include:

-

A fully configured & integrated Jira instance.

-

A “project CLI” that apparently does some useful stuff.

-

A GitHub Actions workflow that performs all kinds of build & deployment tasks.

The assumption is that these are also fully documented someplace, and that they work together to implement the version control process described above.

This might sound like it’s a trivial point but it isn’t. After all, how do you know what the dependencies of your version control process are if you haven’t written it down?

Once you have written it down, those dependencies are in plain sight, and you can follow the breadcrumb trail to get the rest of your process documented as well!

Leave a comment